A Wonderful Script ?

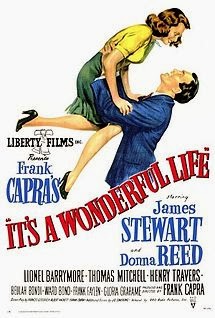

In 1946, audiences did not much like the movie "It's A Wonderful Life," and critics were pretty tepid, too. Some were fond of it, sure. But a lot of them hated it, and it probably would've garnered a great big green SPLAT on the tomato-meter, if Rotten Tomatoes had been a thing back then. The nation was reeling from WWII, and whatever the populace wanted in a movie, "It's a Wonderful Life" was not it.

Now, of course, it's considered a classic, and currently ranks at #11 on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 best American films ever made.

The world is full of stories like these - stories of works of art (or even bodies of work) that in their time were widely reviled, but later were accepted, and even revered.

I think perhaps we love these stories so much because we like to think of ourselves as being under-appreciated by the world at large. We enjoy the thought that if art can be undervalued, then maybe we are just as special as our (esteem-psychology-driven) mothers always assured us we were, and that the world is just too dumb or too preoccupied with itself to appreciate us the way we deserve.

History will vindicate us! We will matter... eventually!

What's not nearly as interesting to us are the stories of all the artists who made things that were received poorly in their time, and the time after, and the time after that. It's fine that these people had their little make-stuff hobbies, we think, but until we see that rubber-stamp of popular acclaim, well - it's easier to just think that they merely didn't have "it." That they're nothing nearly so special as, say... us.

A week ago, in my post Guess I'll Go Eat Worms, I wrote about getting a 3/10 rating on my script PINK from a paid reader at the Black List website. This hurt, even though I did not really think such a rating was justified. I dealt with this in a number of ways:

He said that "It's entirely possible for readers to have divergent reactions to scripts and that another reader would love it. It doesn't necessarily invalidate either review. There are some scripts that are just polarizing. And ultimately there's a degree of subjectivity to evaluating screenplays." He then added that if there were any factual errors in the review, they'd be happy to address them.

Kinda what I expected, and it makes sense, too. Criticism is somewhat subjective.

But then I thought, wait a minute. Is that for real? Is it true that if critics say two diametrically opposed things about a work of art, it doesn't necessarily invalidate either of them? How is that possible?

If I say the sky is blue and you say it's yellow, doesn't one of us have to be right?

Well, not necessarily. Since color is a function of perception, it could be the case that when we look at the sky, I really am seeing something something that I perceive as "blue," and you really are seeing something that you perceive as "yellow." Just because the vast majority of people are on my side and agree that the sky is something we'll agree to describe using the word-symbol "blue," that doesn't mean I'm right. For long periods of time, the majority held that the sun rotated around the world, and now we all know that the opposite is true. So maybe the sky is yellow. If we're not making perception statements, such as "I perceive the sky to be blue" (which would be more accurate), then our position cannot be taken to be True a priori - we'll have to argue the point.

Nevertheless, the fallibility of perception doesn't seem to me to be a great argument against the idea that one of us has to be wrong when we say opposite things. Perhaps I chose a bad example, though, since we could both be wrong - the sky could actually be green.

That's not the point, though. It's not about arguing who's right. That's criticism, not creativity, and it bores me. I would much rather have art be evaluated on a more openly subjective, experiential basis.

Still, the idea that we cannot objectively evaluate a work of art bothers me.

Perhaps this is a practical choice on my part. I believe in objectively good or bad (or shall we say, "worse" or "better") choices in art because I need to believe that - in order for there to be any sort of meaning to my attempts to improve my own work. How can I become a better writer, if "better" doesn't really exist?

But maybe that's not it at all. Maybe my reasons are more nefarious. Maybe it's pride - my desire to live in a world where I am an arbiter of value for the many. I've certainly been accused of that on this blog, before. Or maybe I'm afraid of a world without edges. Maybe I need there to be good and bad art so that the world will make sense - so that there will be some sense of justice in whether I do or don't "succeed" at what I'm trying to do, here.

I'm happy to agree that all art has value, and that critics who denigrate in a way that stifles the creative impulse deserve to be dipped in hot tar and shaped into garden sculptures... but at the same time I want to live in a world where excellence is affirmed and encourage by the culture at large.

Is it worth pouring your heart and soul into artwork that is then never valued?

Who knows?

Not me.

What I do know is that if you really, really want a brick wall to fall over, you've got to be willing to bash yourself against it for as long as it takes. So I responded to the Black List guy again, explaining that I wasn't trying to be difficult, but that it seemed to me that if someone was making ill-considered script reviews in their name, then they'd want to know about it. They did not, of course, concede my point. But they did give me a coupon for another free review, which could end up demonstrating a couple of very valuable life-lessons.

1) The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

2) Josh Barkey is a glutton for punishment.

We shall see.

Now, of course, it's considered a classic, and currently ranks at #11 on the American Film Institute's list of the 100 best American films ever made.

The world is full of stories like these - stories of works of art (or even bodies of work) that in their time were widely reviled, but later were accepted, and even revered.

I think perhaps we love these stories so much because we like to think of ourselves as being under-appreciated by the world at large. We enjoy the thought that if art can be undervalued, then maybe we are just as special as our (esteem-psychology-driven) mothers always assured us we were, and that the world is just too dumb or too preoccupied with itself to appreciate us the way we deserve.

History will vindicate us! We will matter... eventually!

What's not nearly as interesting to us are the stories of all the artists who made things that were received poorly in their time, and the time after, and the time after that. It's fine that these people had their little make-stuff hobbies, we think, but until we see that rubber-stamp of popular acclaim, well - it's easier to just think that they merely didn't have "it." That they're nothing nearly so special as, say... us.

A week ago, in my post Guess I'll Go Eat Worms, I wrote about getting a 3/10 rating on my script PINK from a paid reader at the Black List website. This hurt, even though I did not really think such a rating was justified. I dealt with this in a number of ways:

- I wrote my "Guess I'll Go Eat Worms" blog post.

- I got a hug from my mom.

- I went on Twitter and asked a working screenwriter I follow why he keeps publicly endorsing the Black List website as being somehow superior, when their hired readers are just as likely to be wrong as the readers of any other service, or contest. His response was that "No one bats 1,000" (true), and that as a general principle, I should "stress criticism over praise" (also true, although I doubt it's advice he's given himself when his films are being eviscerated by critics).

- Lastly, after waiting a few days to see if my POUNDERS script would move past the finals to win the ATLFF screenwriting competition (in order to have more ammunition proving how awesome I am: FAIL), I wrote a letter to the Black List people laying out all the reasons why I thought that a 3/10-I-hate-this-piece-of-crap-script rating was unjustified.

He said that "It's entirely possible for readers to have divergent reactions to scripts and that another reader would love it. It doesn't necessarily invalidate either review. There are some scripts that are just polarizing. And ultimately there's a degree of subjectivity to evaluating screenplays." He then added that if there were any factual errors in the review, they'd be happy to address them.

Kinda what I expected, and it makes sense, too. Criticism is somewhat subjective.

But then I thought, wait a minute. Is that for real? Is it true that if critics say two diametrically opposed things about a work of art, it doesn't necessarily invalidate either of them? How is that possible?

If I say the sky is blue and you say it's yellow, doesn't one of us have to be right?

Well, not necessarily. Since color is a function of perception, it could be the case that when we look at the sky, I really am seeing something something that I perceive as "blue," and you really are seeing something that you perceive as "yellow." Just because the vast majority of people are on my side and agree that the sky is something we'll agree to describe using the word-symbol "blue," that doesn't mean I'm right. For long periods of time, the majority held that the sun rotated around the world, and now we all know that the opposite is true. So maybe the sky is yellow. If we're not making perception statements, such as "I perceive the sky to be blue" (which would be more accurate), then our position cannot be taken to be True a priori - we'll have to argue the point.

Nevertheless, the fallibility of perception doesn't seem to me to be a great argument against the idea that one of us has to be wrong when we say opposite things. Perhaps I chose a bad example, though, since we could both be wrong - the sky could actually be green.

That's not the point, though. It's not about arguing who's right. That's criticism, not creativity, and it bores me. I would much rather have art be evaluated on a more openly subjective, experiential basis.

Still, the idea that we cannot objectively evaluate a work of art bothers me.

Perhaps this is a practical choice on my part. I believe in objectively good or bad (or shall we say, "worse" or "better") choices in art because I need to believe that - in order for there to be any sort of meaning to my attempts to improve my own work. How can I become a better writer, if "better" doesn't really exist?

But maybe that's not it at all. Maybe my reasons are more nefarious. Maybe it's pride - my desire to live in a world where I am an arbiter of value for the many. I've certainly been accused of that on this blog, before. Or maybe I'm afraid of a world without edges. Maybe I need there to be good and bad art so that the world will make sense - so that there will be some sense of justice in whether I do or don't "succeed" at what I'm trying to do, here.

I'm happy to agree that all art has value, and that critics who denigrate in a way that stifles the creative impulse deserve to be dipped in hot tar and shaped into garden sculptures... but at the same time I want to live in a world where excellence is affirmed and encourage by the culture at large.

Is it worth pouring your heart and soul into artwork that is then never valued?

Who knows?

Not me.

What I do know is that if you really, really want a brick wall to fall over, you've got to be willing to bash yourself against it for as long as it takes. So I responded to the Black List guy again, explaining that I wasn't trying to be difficult, but that it seemed to me that if someone was making ill-considered script reviews in their name, then they'd want to know about it. They did not, of course, concede my point. But they did give me a coupon for another free review, which could end up demonstrating a couple of very valuable life-lessons.

1) The squeaky wheel gets the grease.

2) Josh Barkey is a glutton for punishment.

We shall see.

Some stuff is clear: gravity takes things towrads the center of the earth; hitting yout thumb with a hammer hurts; being a liar also hurts loved ones (diff kind of hurt) and so on.

ReplyDeleteArtistic pieces are not valued beside absolutes. They are of a different nature. No words can describe it. Subjectivity is a part of the process, and moral upbringing too - (remember the pee in a jar that made the headlines?) and cultural experiences from one's past.

Oh, Josh. You are loved and even adored by some. Be brave and tough it out. Hugs, Auhnt Aur